We partner with nonprofits to help them grow, and as we’ve realized, catalyzing and then sustaining significant growth in organizational performance and impact is hard work. After working with hundreds of nonprofits over a couple of decades, we’ve recognized patterns in how organizations respond differently to the change process.

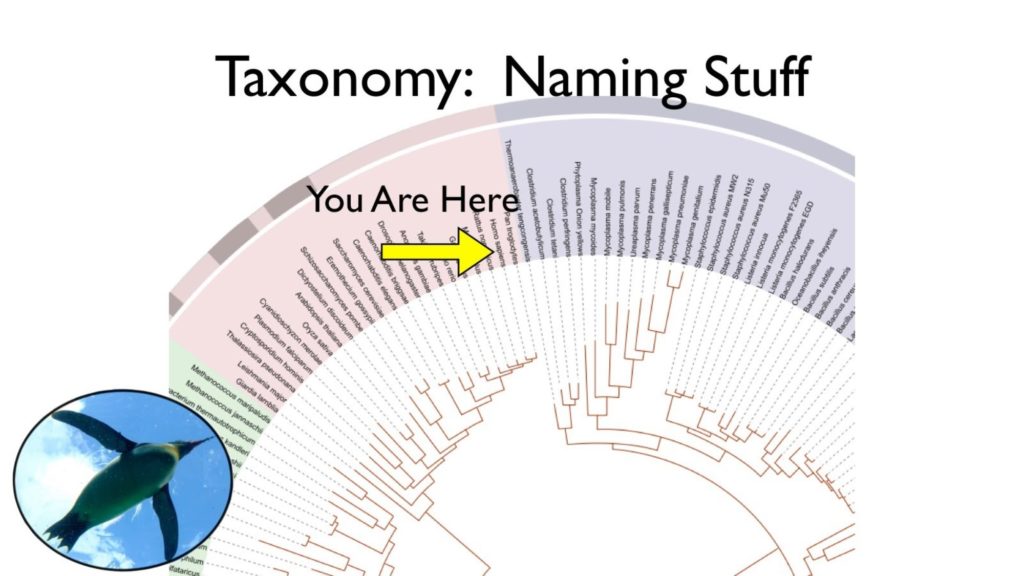

So here is an unscientific set of observations, an informal effort to segment the non-profit sector into its major phyla, presented with the caveat that more accurate speciation requires description as varied as nature itself.

1. Social Clubs — the most common type of nonprofit: these are small organizations, typically under 500K in annual revenue, that come together around a common cause but whose mission is also equally weighted on providing a foundation for friendship and community. They deliver modest amounts of good work and raise money among friends and family to do something meaningful. There’s little fancy language, and they are happy with delivering marginal benefits at the community level.

- Examples: PTAs; Lions Clubs; The Awesome Foundation.

- These groups offer tremendous collective richness and benefit to the world. We applaud them and even participate in them ourselves.

2. Feel Goods — these orgs are very similar to social clubs, but they differ chiefly in that they use the rhetoric of solving big challenges to create an illusion of significance. While there may be plenty of aspirational language, little of it is backed up by performance. So many aspects critical to delivering impact are absent: measurable goals; accurate strategy; data-driven performance analysis systems; adequate capital; driven and capable staff and directors; and numerous other pieces required for translation desire into action and results.

- Any type of organization can fall into the “words, not deeds” trap, but it can be very difficult to tell a performer from a pretender. These are not bad people running these organizations, but they do appear to be fixated more on generating and discussing lofty ideas than funding and executing them. These orgs function primarily as a social circle and support group, with dominant cultural elements being 1) fear of change, 2) risk aversion, and 3) a preference for reflection and analysis over action and experimentation.

- These groups may appear to be doing valuable work, but they have profound cultural or performance barriers to achieving substantial levels of impact that are often hidden from view.

3. Enduring CBOs (Community Based Organizations)— the meat and potatoes of the non-profit sector, there are tens of thousands CBOs, among the best threads in the fabric of American society. They have clear bounds for their services and seek to deliver quality at an intentional and well defined scale, typically at the neighborhood, municipal or at most a regional level. They often have significant unrealized organizational potential.

- Examples: day care centers, independent schools; clinics, homeless shelters & food banks; regional theater, art, museums; farmers markets.

- They often suffer from performance or revenue pain, and they would do well to learn enterprise-class business modeling and execution. They should look outside the nonprofit sector and learn how all high performing businesses function if they wish to reach their full promise and potential.

4. Dysfunction Junctions — Tolstoy opens Anna Karenina with the line “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy families is unhappy in its own way.” Just so, all high performing organizations share many of the same characteristics, but dysfunctional ones all have unique and often colorful reasons for their ills. Disengaged boards; poor HR practices; micro-managing or absentee leadership; low pay; ineffective fundraising strategy; poor financial controls; pathological or bureaucratic leadership… the list is very long and rather depressing. There is even a small set of extreme negative outliers with Dark Triad leadership. See this exposé for examples of what these malevolent minds can do at the helm of a nonprofit.

- Ken Stern’s brilliant muckraking With Charity for All exposes this dark side of the non-profit sector.

- Nonprofits aren’t alone in suffering from dysfunction—all organizational types, including private sector businesses and government agencies—fall prey to poor leadership, sloppy execution, etc.

5. Gutsy Aspirants — there are many thousands of these organizations. They are among the most promising, scalable nonprofits in the sector, ranging in size from start-ups to $10 or so annually. They have promising program models and are willing to work hard to get it to scale. There’s passion, yes, but also evidence of discipline, focus, teamwork and committed leadership.

- Social impact investors, savvy philanthropists, values-driven corporations and critically minded donors look to these orgs as their primary means of creating social impact.

- We love working with these groups. Organizations ready for the entrepreneurial journey can, with hard work and focus, deliver tremendously meaningful social solutions able to scale to the size of the challenge.

6. Staid Institutions — These are established regional orgs or affiliates of a strong national brand, but many are running on inertia. If they were trees, they would look healthy on the outside but have serious problems with rot on the inside, and they need triage before they come down in the next windstorm.

- Some longstanding nonprofits and national associations have very strong brands and little competition, and without rigorous oversight, serious problems can occur out of sight of donors and even staff.

- Expert analysis and close partnership at the executive and board level are often necessary to diagnose organizational malfunction or lost opportunity before the problem grows.

7. Big Business — major research institutions; the largest national associations; large hospital systems. In the nonprofit sector, these organizations comprise 4% of the nonprofit population but control 85% of the resources. This is a surprising concentration of wealth and power in fewer that 30,000 of the current 1.4 million nonprofits – a concentration of money and influence even more unequal than the distribution among US households.

- While these organizations constitute the backbone of the sector, because so many of them so utterly dominate their respective spaces, the resulting lack of competition leads to hubris, monopolistic behavior, mission drift and self-dealing. For example, The Red Cross has been widely criticized; a particularly disturbing story is how Phil Knight turned the University of Oregon into a subsidiary of Nike.

- These organizations prove that its possible to make tons of money, run effectively and efficiently, and maintain integrity and social purpose (except when you get corrupted by all that money, which happens). Smaller nonprofits can learn from and adapt their growth strategies—they, too, were once small.

This list isn’t a comprehensive, of course, but hopefully it is a helpful tool to make sense of a tremendously varied sector filled with many excellent and virtuous souls, a space in which it is an honor to work.