Strong board governance is one of, if not the most, critical success factors for nonprofit organizations. Running an organization is hard, complex work, and the collective guidance and oversight provided by a brain trust of diverse, experienced leaders is essential if the organization is going to make significant mission progress.

However, too many nonprofit board members don’t fully understand what it means to be a director of a nonprofit corporation, and as a direct consequence of this, organizational performance and impact is severely constrained. Altruist’s consultants have engaged with hundreds of boards of directors for organizations of all shapes and sizes, nationally and internationally. We’ve worked with thousands of incredibly generous and well-meaning people working hard to support their organizations. But as we’ve seen, the vast majority of boards need a substantial amount of education before they can function effectively as corporate directors and fiduciaries.

While there are untold numbers of consultants and organizations along with a sizeable literature that all purport to enhance nonprofit board performance, two constraints prevent the right information from getting into the hands of the directors who need it.

The first is lack of bandwidth. Nonprofit directors are already time-strapped volunteers. While most boards readily agree they can perform better, collective analysis and self-improvement usually take a distant back seat to any number of pressing organizational concerns. Here as elsewhere, the important is crowded out by the urgent.

The second constraint is something we all experience these days: information overload. These days, even mundane tasks like shopping for a new dishwasher or picking out a movie on Netflix can trigger anxiety and decision fatigue. Open your laptop and you are clobbered by too much choice and too many websites screaming “pick me! This is worth your time!” (By the way, for a fascinating discussion of how we all became information overload victims, check out Tim Wu’s The Attention Merchants.)

So if when it comes to something far more complex — such as nonprofit board performance — we are already all attention-deprived, and for complex challenges like this one, few know where to even begin. How do we tell which resource or consultant is the right one? Spend enough time on Google and, like so many other subjects, you’ll find a confusing superabundance.

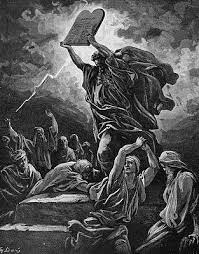

What do we do? As the famous French polymath Blaise Pascal apologized to his friend, “I am sorry I wrote you such a long letter. I did not take the time to make it short.” So what’s needed is clear, concise, comprehensive and concrete information to point boards of trustees in the right direction. Here’s our attempt to boil down our best advice for boards in a memorable and actionable way: two “commandments.”

Commandment One: Thou Shalt Have at Least Two Successful Entrepreneurs on Your Board.

It is hard to overstate the value of experience gained by successfully growing a company. Only 4% of for-profits ever make it past $1m in annual revenue, so leaders who have built and grown larger organizations possess wisdom that even very smart, experienced managers don’t.

This experience is essential for nonprofit boards as most nonprofits are far smaller than they need to be to solve the problems they are addressing. Among our firm’s large & diverse client base, we continue to measure large positive differences in organizational performance and impact among the subset of organizations that enjoy experienced entrepreneurs on their board. We measure this quantitatively with our firm’s Organizational Performance Index, which benchmarks nonprofits on a 1 to 100 scale that measures organizational capability to deliver social impact at scale. In over 100 assessments, the median performance score for all organizations is 42. However, when considering only the subset of organizations with successful entrepreneurs on the board, the average score is 64 – over 50% higher. This is no accidental correlation. We know from thousands of hours inside these organizations that the positive influence entrepreneurs bring to their nonprofit boards is striking and obvious.

To be clear, this acumen is far from every skill that good governance demands. When we guide our clients to accelerated impact, we make sure there is board-level expertise in all the major organizational domains: marketing, sales, operations, HR, accounting, law, and so forth. That said, starting with established entrepreneurs who know how to knit all these diverse skills together into a strong governance team remains perhaps the single most important success factor we’ve seen around governance.

Commandment Two: Thou Shalt Direct Your Nonprofit Like Your Retirement Depends On It.

Cindy CEO might be a successful entrepreneur, but if she sits on her local arts board just so she can talk about it at cocktail parties and make a splashy donation at the gala, she’s not the director her organization needs. The performance killer we see repeatedly, even for nonprofits with skilled executives at the helm, is a lack of engagement and accountability at the Director level. “It’s a nonprofit,” we often hear sotto voce, as if that single label is an explanation for not overseeing the organization with the rigor and expectations one would typically reserve for a for-profit enterprise. As a result, any number of constraints such as low staff pay, ambiguous performance measurement, inadequate risk management, lack of clear goals, compliance problems and others are accepted as normal byproducts of tax-exempt status. Without active leadership and direction from the board, these and any number of other solvable organizational barriers remain unaddressed.

In truth, the only difference between a for-profit and nonprofit is nonprofits don’t have equity. Nonprofit directors exercise 100% legal control over their organizations, but the lack of direct ownership and profit motive means no one is losing their shirts when organizational performance suffers.

Combine the “it’s just a nonprofit” excuse with a lack of profit motive and we’ve got what we see now: hundreds of thousands of nonprofit boards that are disengaged or unable to lead scalable organizations. We see evidence for this in our Performance Index, which includes a survey question to all board members: “This organization is my #1 social cause and my top priority for my time, treasure and talent.” In fewer than 20% of the organizations we’ve measured do the majority of board members respond that they agree strongly with this statement.

While this stance is understandable – directors may sit on multiple boards, they are unpaid volunteers, they may have more than one important cause, etc. – this disengagement must not be tolerated if the organization is to achieve mission progress. Being on a board is difficult, complex work. There are at least ten separate management domains that need simultaneous monitoring and evaluation, and even one or two members who don’t show up on time or read the board packet are instead actively functioning as performance killers. Directorial neglect is malignant.

After years of reflecting on the challenges of overcoming these profound barriers to board member selection and engagement, we’ve devised a simple thought experiment for directors: “Imagine your organization’s financial surplus is the only funding for your retirement. What would you do differently as a director?” The wheels start to turn immediately. “Well, for starters I’d strengthen the executive team. Then I’d invest a lot more in sales and marketing. And we need to focus on the quality of our program, maybe get some independent evaluations…” These responses are often strikingly similar to some of our own recommendations.